Editing or cutting is the act of taking two separate shots and joining them together so that one shot “cuts” to the other. This relatively simple act becomes one of the most important and complex aspects of film art. We will be using the term “cut” as both a verb (as in “The editor cuts from a close up of the phone to a long shot of the window.”) and as a noun (as in “This cut is a dissolve.”). Simply put, a cut (as a noun) is any type of edit, but in your Exam 2, avoid using cut if you can use a more specific term.

The editor is the person in charge of assembling the various shots created during the production process into a final cut. During what is called “postproduction,” the editor will work closely with the director and will oversee assistant editors, negative cutters (if they are using film stock rather than shooting digitally) and other staff.

While today it is common for directors to work closely with editors, it was not always the case in film history. Before the 1960s, during the heyday of the studio system, most directors did not have control over the editing of their films. Only directors who had achieved a high level of success (DeMille, Hitchcock, Ford, etc.) could have a place in the editing room. Since the 1960s, this has changed (we will discuss why in class); directors now have some level of control over the editing process. At the very least, they will work closely with the editor to assemble the final cut of the film. This is not to denigrate the role of the editor. More so, it shows the importance of the editor in that some directors will take on the role themselves. Others will work with the same editor over the course of many films; Thelma Shoonmaker has been Martin Scorsese’s editor for about fifty years!

The Russian Montage Movement

The Russian Montage Movement (also called Soviet Montage and Constructivism) exerted a huge influence over the course of editing and filmmaking in general. Please read this summary of the movement and three of its most important filmmakers, Kuleshov, Eisenstein and Vertov:

Plus, take a look at this short film, detailing the Russian Montage movement and its influence. You do not need to know the additional terminology he includes:

Spatial, temporal, graphic, rhythmic, and conceptual relations

Generally, film scholars (influenced by David Bordwell) discuss five basic categories for the relationship between two shots joined by an edit: spatial, temporal, graphic, rhythmic, and conceptual relations

spatial relations

This term covers all the ways that editing can manipulate a viewer’s sense of the space within a shot and the space implied beyond the frame. For example, if you cut from a shot of the Golden Gate Bridge to a shot of a man walking down a street, the viewer will likely assume that the street is in San Francisco. This is called the Kuleshov effect.

As detailed in Sharman’s chapter, Lev Kuleshov was an influential filmmaker and instructor in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution in 1917 and taught some of the greatest members of the Russian Montage Movement. You can read about his famous experiment involving editing (referred to as the Kuleshov experiment) in the links above concerning the Russian Montage Movement; Sharman includes the original experiment itself!

The Kuleshov effect refers to how editing can create space. The Kuleshov effect is simply that if not given a reason to think otherwise, audiences (most likely) will assume that two shots occupy the same space. Borrowing from Kuleshov’s experiment, if you cut from a shot of a person’s face to a bowl of soup, the viewer will assume that they occupy the same space, as long as there is nothing to indicate otherwise (e.g. a radical shift in the background, a change from color to black and white, etc.).

temporal relations

This term covers all the ways that editing can manipulate time. As you can see, film production has developed several terms for this aspect, pointing to the power of editing to manipulate the viewer’s sense of time.

flackback, flashforward

A flashback involves two cuts: one cut to the past/an earlier event in the narrative and another cut back to the present. These cuts are often (but not always) fades or dissolves. A flashforward is the same thing, except the cut is to a future event in the narrative and then back to the present. Flashforwards are much less common and tend to disrupt continuity editing (see the discussion below). Please be careful: an edit that moves forward in time is not a flashforward unless it eventually moves back to the present. There may be other edits within a flashback or flashforward, but the two important cuts (the one that takes the viewer to the past or future and then back to the present) are fairly close together; generally, flashbacks and flashforwards are not very long, with a few notable exceptions.

elliptical editing

Elliptical editing is not a particular kind of cut but more so any edit that creates a temporal ellipsis, a jump forward in time. Many edits will do this. For example, shot A is of a woman walking toward her front door; shot B is her at the door (we will refer to this later as a match on action). The brief seconds between her walking toward the door and reaching the door are deleted. Since many edits advance time in this way, we should reserve the term “elliptical edit” for edits that create a more significant jump forward. Check out this example from Citizen Kane:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/bnd/clips/elliptical-editing-in-citizen-kane/view

Another example is the link below from 2001 (which is also an example of a graphic match).

Punctuation shot is another term for elliptical editing, although some sources will use it to describe dissolves, wipes (see below) or similar edits that signify the passage of a considerable amount of time.

empty frame edit

A very common elliptical edit, usually used when characters are moving from one location to another. For example, a character leaves her house. After she leaves the frame, you hold for just a second or two on the “empty frame” of the space, absent the character. You then cut to a hotel lobby once again absent of the character (the second “empty frame”). After a second or two, the character walks into the lobby. The empty space of the first shot matches with the empty space of the second shot.

graphic relations

Graphic relations refer to how the graphic qualities of one shot relate to the graphic qualities of the next. By graphic qualities, we mean aspects such as color, the movement of figures, lighting, etc. The most common way that graphic relations appear in editing is through a graphic match. In a graphic match, the shots joined by an edit share some kind of graphic similarity. This similarity needs to be obvious and powerful. We would not call an edit a graphic match if the similarity is minor or not immediately noticeable. Here is one of the most famous graphic matches of all time (with a bit of voice over commentary) from Kubrick’s 2001:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/2001.mov/view

Kubrick cuts from the bone to the similarly shaped space station, creating a graphic match (notice they are also matched by their position in the frame) as well as an audacious elliptical edit.

rhythmic relations

Rhythmic relations describes how the pace of editing has various rhythms, depending on the mood or tone being created. Take a look at this clip from George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road and try clapping every time there is an edit. Doing so will help you feel the shifts in rhythm:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/pfgonder/clips/mad-max-fury-road/view

conceptual relations

To understand what we mean by “conceptual relations,” we need to return to the Kuleshov experiment, which shows how editing can do more than create spatial relations—it can alter or effect how the viewer thinks or feels about what is shown on screen. In Kuleshov’s experiment, he cuts from a person’s face, to a shot of bowl of soup, and then back to the same shot of the person’s face. The person never actually sees the soup, and the two shots of the face are the same. It is possible the audience may “read into” the third shot, seeing hunger in the actor’s face, even though it is the same shot as the first and the actor never actually saw the soup. Hitchcock understood this idea to an incredible degree, stating (sardonically) that “actors are cattle” (or should be “treated as cattle”), implying that editing created an actor’s performance. Check out this video of Hitchcock explaining how editing can create conceptual relations:

We can take this idea farther and discuss how editing can create intellectual, emotional, or psychological effects, prompting the viewer to feel or think in a certain way (although it is never possible to predict how an audience will react). D.W. Griffith used psychological editing to mirror what a character was thinking or feeling, cutting from a man looking forlornly at a picture of his fiancé to that other character, sitting at home, far away from him. Below, we will discuss Eisenstein’s ideas of “intellectual montage” and how editing can generate political thought or action. See Sharman’s description of subject match as a way that editing can create conceptual relations, how it can connect two shots through their shared meaning.

Transitions between scenes

Before we tackle how editing is used within a scene, let’s talk about common edits between scenes, edits that connect scenes together (other than a simple cut, which is often used). It is important to note that these edits have uses other than connecting scenes, but they are used most often in this regard.

fade (in and out)

In a fade edit, the screen goes to black or white; the image fades away to nothing. This is called a fade out. Then, the next shot fades in. Here is a fade edit from King Vidor’s Gilda:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/dsbaldwin32/clips/gilda-vidor-1946-2014-turn-yourself-in

Editors can combine a fade with a cut. For example, an editor could cut to black and then fade in or fade out and then cut to a new shot.

iris (in and out)

An iris edit uses a mask over the lens that can constricts in a circular shape (an iris mask). This type of mask was used in early cinema to draw attention to a certain part of the screen; the iris could close, leaving the screen black except for the circle, showing the desired part of the image (think of the opening to pretty much every James Bond film when you see Bond in silhouette in the circle of light caused by a rifle scope). An iris edit is when the iris constricts to nothing and then opens onto a new scene. Here is a brief example from A Christmas Story:

As with a fade, an editor could iris in to black and then cut to a new shot or cut to black and then iris out.

dissolve

It is important not to confuse a dissolve with a fade (a common mistake). In a fade edit, the image gradually (although usually quickly) fades out or in, but there is a moment between the shots that is blank—the two shot do not overlap. In a dissolve, they do so. A dissolve allows the two images to be superimposed onto each other as one fades away and the other fades in. Here is a dissolve from Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/pfgonder/clips/eyeline-match-and-dissolve/view

Here’s a dissolve edit from His Girl Friday. Notice that the dissolve implies (as they often do) that time has passed. In this way, dissolves are often elliptical in nature.

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/bnd/clips/dissolve-in-his-girl-friday/view

wipe

In a wipe edit, one image “pushes” the other off the screen. Usually, the second shot moves laterally, “wiping” away the first shot. Here is a wipe from Howard Hawk’s His Girl Friday:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/wipe-critical-commons-1.mp4/view

Wipes can move in any direction: diagonally, from top to bottom, etc.

invisible wipe and wall cut

Another kind of wipe is called an invisible wipe. This edit occurs when an object moving across the screen acts as the border between the two shots. Here is an example from Citizen Kane in which a bar hides the transition from shot A to B.

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/anansi00/clips/film-citizen-kane-opera-invisible-wipes

Here is an excellent example from Jaws:

There is a “showier” version of the invisible wipe; I am not sure if it has a separate name. In the examples above, the object that passes over the frame, “wiping” out shot A for shot B is blurred or not noticeable (thus the term “invisible”), but the same effect can be achieved with an object that the viewer notices. For example, in shot A, a woman walks from left to right, her body extending from the bottom to the top of the screen; in front of her is Shot A (let’s say, a street in New York City), but behind her is Shot B (a field in rural Nebraska). In City of God, the first shot is of a street in the 1960s; a car passes by—in front of the car is the street in the 1960s, but behind the car is the street years later:

https://criticalcommons.org/view?m=fxCto7iYu

A wall cut works in the same way, but the barrier is a wall and the camera moves, not the object. Unlike the examples above, wall cuts are almost always used to move from one space to a different space. For example, the camera tracks from left to right, through a room, or some enclosed space. Once the camera passes by a wall (as if the “fourth wall”—the wall between the characters and the audience—does not exist), the wipe occurs. On the other side of the wall (shot B) is a new space, not connected to the space in shot A. Shot A could be a suburban living room; Shot B could be a room in a military facility. A wall cut make it seem as if the two spaces are separated by only a wall, but the two rooms are in different locations.

Continuity Editing/Invisible Editing/Classical Hollywood Editing

Early on in American film history, filmmakers working in Hollywood developed a system of editing that came be to called a variety of terms: continuity editing, invisible editing, seamless editing, or (in historical retrospect) classical Hollywood editing. The driving goal of this system is to edit in a way that achieves the objective of the scene (whether it be a quiet romantic moment or a quick paced gun fight) while preserving spatial and temporal continuity. In other words, classical Hollywood editing strives to have an effect on the viewer while remaining invisible, editing from shot to shot in a way that makes sense, without confusing the viewer concerning the space or chronology of the scene. The edits should move the viewer’s attention from shot to shot without them noticing. Continuity editing attempts to suture (see more on this concept below) the viewer into the film, as a passive observer. It works to create a product for the audience to watch that draws them into the narrative. As we will discuss in contrast to the Russian Montage Movement, the viewer should not notice the edits, even as it guides their attention and shapes their experience of the film. The goal of continuity editing is to maintain spatial and temporal continuity so that the viewer is not confused (or at least for long) about the space of the scene and the time frame of the events.

Early on in American film history, filmmakers working in Hollywood developed a system of editing that came be to called a variety of terms: continuity editing, invisible editing, seamless editing, or (in historical retrospect) classical Hollywood editing. The driving goal of this system is to edit in a way that achieves the objective of the scene (whether it be a quiet romantic moment or a quick paced gun fight) while preserving spatial and temporal continuity. In other words, classical Hollywood editing strives to have an effect on the viewer while remaining invisible, editing from shot to shot in a way that makes sense, without confusing the viewer concerning the space or chronology of the scene. The edits should move the viewer’s attention from shot to shot without them noticing. Continuity editing attempts to suture (see more on this concept below) the viewer into the film, as a passive observer. It works to create a product for the audience to watch that draws them into the narrative. As we will discuss in contrast to the Russian Montage Movement, the viewer should not notice the edits, even as it guides their attention and shapes their experience of the film. The goal of continuity editing is to maintain spatial and temporal continuity so that the viewer is not confused (or at least for long) about the space of the scene and the time frame of the events.

The Hollywood system described below has its origins in the earliest parts of American film history. In 1903, Edwin S. Porter makes “The Great Train Robbery,” a short film featuring some key aspects of continuity editing (most notably cross cutting), although in a crude fashion.

D.W Griffith had been experimenting with these editing practices in the multitude of short films he made for Biograph studios By 1915, with the incredible success of The Birth of a Nation, the continuity system of editing had been enshrined as the dominant mode of editing for Hollywood. In Birth of a Nation, Griffith employs much of what we associate with modern editing. For the climax of his next film, Intolerance (1916), Griffith even crosscuts between four different plot lines, in four different historical eras.

Two important notes. First, Porter and Griffith are often cited as “creating” invisible editing, but research shows that these practices were being used across the industry before they made their respective films. While they did not create Hollywood classical editing out of nothing, their films certainly worked to popularize it.

Second, while Birth of a Nation is a key text in film history (American or otherwise), it is also an undeniably racist film that presents the end of slavery as a tragedy and features the Klu Klux Klan as the heroes (see Spike Lee’s use of this film in BlackKKKlansman). If you watch, please be warned. As a director, Griffith presents an interesting enigma. After Birth of a Nation, he made two films that are clearly statements (successful or otherwise) against racism: the previously mentioned Intolerance and Broken Blossoms (1919), a film about an interracial love affair.

Continuity editing follows a certain pattern, although this pattern can be modified or adapted for the needs of an individual scene.

A scene begins with an establishing shot.An establishing shot gives the viewer a sense of the space in which the action will take place. It is usually a long shot or a shot of great enough distance to reveal the space of the scene.

It is possible to have telescoping establishing shots, multiple establishing shots at the start of a scene that move from inward toward the final space: for example, a shot of the city, a shot of a building, a shot of a room (which is our final establishing shot).

At times, the establishing shot may be the same as the master shot. Here is the Wikipedia definition of the master shot:

A master shot is a film recording of an entire dramatized scene, from start to finish, from an angle that keeps all the players in view. It is often a long shot and can sometimes perform a double function as an establishing shot. Usually, the master shot is the first shot checked off during the shooting of a scene—it is the foundation of what is called camera coverage, other shots that reveal different aspects of the action, groupings of two or three of the actors at crucial moments, close-ups of individuals, insert shots of various props, and so on (“Master Shot”).

An establishing shot does not need to be a master shot in that an establishing shot does not need to show the entire space, just enough of it to set up spatial continuity.

Now that the space of the scene has been established, the breakdown starts. The action of the scene begins, and as that occurs, the space is “broken down” by the various edits necessary to capture that action.

What follows are the most common edits that occur during the breakdown.

cutting on action/match on action

In a match on action, shot A starts an action, and shot B completes that action. For example, a woman throws a football, and the next shot shows her friend catching the ball. Here are a couple of match on action edits from Howard Hawk’s His Girl Friday:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/fridaymatchonaction2.mp4/view

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/fridaymatchonaction3.mp4/view

In continuity editing, cutting on action will follow the 180 degree rule (see below).

eyeline match

An eyeline match happens when shot A shows a character or characters looking at something, and shot B shows what they see. For example, a character hears the sound of glass breaking and turns to look; the next shot is broken vase on the floor. Some textbooks will make a distinction between a glance-object match and an eyeline match, but for the sake of this class, we will treat them as the same thing. Here is an eyeline match from Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/pfgonder/clips/eyeline-match-and-dissolve/view

Please note that eyeline matches are not necessarily point of view cutting (see below). In the example above with the broken vase, shot B does not have to be from the point of view of the character in Shot A; shot B can be from a different angle, distance, or perspective.

point of view cutting

Point of view cutting occurs when eyeline matches are clearly from a character’s specific point of view. There is often some indicator that it is from a character’s particular and exact point of view (branches in the way, a hand raised in the shot, etc.). Point of view shots are relatively uncommon in invisible editing, perhaps because it is too “showy” and takes the audience out of their objective, omniscient position.

For Exam 2, do not overuse point of view editing. Remember that eyeline matches are not necessarily point of view shots. Plus, a point of view shot must be from a character’s perspective, not an object.

shot/reverse shot

Shot/reverse shots are very common and are used most often to shoot conversations. Shot A is of a character; shot B (the reverse shot) is of different character who occupies the same space. These edits may be right on the axis of action (see below), but they do not have to be. Shot/reverse shots often use over the shoulder shots as well.

Here are shot/reverse shots from Hawk’s His Girl Friday: http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/brettservice/clips/hisgirlfriday_clip3.mp4

Here are shot/reverse shots from Grey’s Anatomy:http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/jbutler/clips/GreysAnatomy20100121.mp4

Since shot/reverse shots are often used for conversations, people may confuse shot/reverse with eyeline matches since the people in the conversation are looking at one another. As a rule (for this class), let shot/reverse shot override eyeline match. In other words, if the editing cuts back and forth in a conversation, call it a shot/reverse shot, not an eyeline match, even if the characters are looking at each other.

reaction shot

A reaction shot is quite simple. It is the shot of a character or characters reacting to the shot that preceded it (we see something, we cut to the character’s reaction). For example, shot A is of a car crash; shot B is of a bystander’s reaction. You might think of it as the opposite of an eyeline match.

cheat cut

Cheat cuts are cuts that “cheat” other elements of the scene in order to create a particular effect or shot. For example, in Meet Me in St. Louis, a character answers the phone, which in the first shot is clearly hanging on the wall, but in the second shot, the camera is positioned so that we can see her face, even though she should be looking directly at the wall (the director—Vincente Minnelli—removed that part of the set so that he could get the shot). Cheat cuts do not break continuity since the audience does not notice the “cheat.”

Examples of cheat cuts from His Girl Friday:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/bnd/clips/cheat-cuts-in-his-girl-friday

The clip above also acts as a nice example of continuity editing as a whole.

head-on/tail-on cut

A head-on, tail-on edit is when a figure (a person, a car, etc.) moves directly at the camera, obscuring the view completely for a second. The next shot is of the same figure moving directly away from the camera, as if the figure has moved through the space of the camera. It is not a head-on/tail-on cut if someone simply walks toward or away from the camera; they have to either block the camera entirely as they walk toward it or begin by blocking the camera entirely and then walk away from it (or a combination of both). Here is an example from the remake of Scarface: http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/m_friers/clips/z-axis-motion-for-a-head-on-tails-away-edit-in/view

insert

Insert can be hard to define since various sources give different definitions. The definition found on Wikipedia is a solid place to start:

“In film, an insert is a shot of part of a scene as filmed from a different angle and/or focal length from the master shot. Inserts cover action already covered in the master shot, but emphasize a different aspect of that action due to the different framing.[1] An insert differs from a cutaway as cutaways cover action not covered in the master shot.”

“There are more exact terms to use when the new, inserted shot is another view of actors: close-up, head shot, knee shot, two shot. So the term “insert” is often confined to views of objects—and body parts, other than the head. Thus: CLOSE-UP of the gunfighter, INSERT of his hand quivering above the holster, TWO SHOT of his friends watching anxiously, INSERT of the clock ticking” (“Insert”).

I’m not sure what “knee shot” is, but the second paragraph of the definition above is important. We can use the term insert to describe a cut-in to a body part or prop (contained within the master shot), usually to draw attention to it.

Any time you have another term (such as eyeline match, reaction shot, shot/reverse shot, etc.) that can be used, use that term instead of insert. For example, if something happens and the camera cuts to someone’s face, you would describe this as a reaction shot, not an insert.

Before we move onto some other common edits, we need to discuss an essential part of the continuity editing: the 180 degree rule (sometimes called the 180 degree system). When blocking a scene, the director will determine the 180 degree line (also called the axis of action). This is the imaginary line drawn between the major components of the shot in order to maintain spatial continuity and screen direction.

It is a simple idea if you think of it in terms of filming a basketball game, or any other sporting event. Imagine watching a basketball game. You are sitting in the bleachers, right at the half-court line; on your left is the Bulls’ basket and on your right is the Warriors’. The axis of action is running between these two baskets, right down the middle of the court. A 180 degree arc is drawn from one basket to the next (basically encompassing your side of the bleachers). You get up and move to the right, but you do not cross the axis of action. In other words, you move to the right, but you don’t go to the other side of the bleachers. Even when you move to the right, the Bulls’ basket is still on the left and the Warriors’ on the right. The same applies if you move to the left (but do not go to the other side of the bleachers). However, if you cross the axis of action and move to the other side of the bleachers, the Bulls’ basket is now on the right and the Warrior’s on the left. Screen direction has reversed. Even if you are standing on your side of the bleachers, almost under one of the baskets, far too one side, the Bulls’ basket is still on the left. If you cross just a few steps to the other side of the basket and cross the axis, the Bull’s basket switches to the right. When people film sporting events, they have to make sure they stay on the same side of the axis when cutting from shot to shot. Imagine if they did not. A player is running from right to left, but if we break the 180 degree rule and cut to the other side, it will look like the player is suddenly running from left to right.

For Exam 2, it can be very helpful to create a story board of your scene. Divide a page into panels, like the page of a comic book. In each panel, make a drawing (no matter how crude) of the shot, signaling movement with arrows.

Story boards are common in filmmaking, and one reason that so many comic book artists live in and around Los Angeles since they get work creating them for Hollywood.

Hitchcock used them extensively, to the point that he found the actual filming process somewhat boring since he felt as if he had already made the film.

It is easy to apply the 180 degree rule to filming conversations. The axis of action and the 180 degree arc is drawn between two people. We can position our camera anywhere in this 180 degree arc, even right on the axis of action (in an over the shoulder shot), and screen direction is maintained. See the image below from DOAA2 Media Studies:

Notice that in shots 1, 2, and 3, the person with blond hair is to screen right, and the person with brown hair is to screen left. In the shot that breaks the axis of action/jumps the line, their positions have reversed.

Here’s a video explaining the 180 degree rule: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bba7raSvvRo

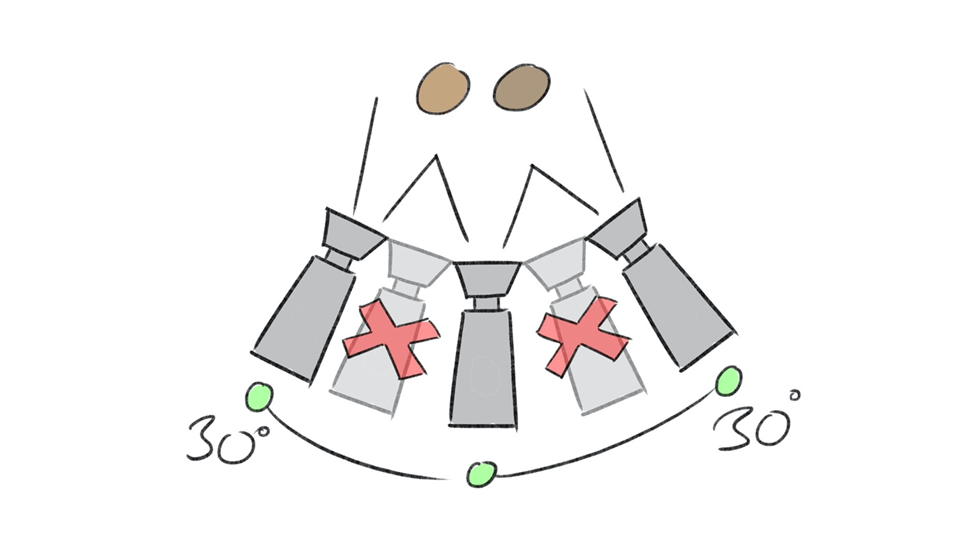

30 degree rule

The 30 degree rule applies to multiple shots of the same figure or object. It operates on the idea that two different shots of the same figure or object need to be different enough for the viewer to recognize them as two different shots. If the two shots are too similar, the edit will be a jump cut (see the definition below), and the edit will appear jagged and obtrusive rather than seamless and invisible. If the two shots are significantly different, the audience will easily recognize the second shot as a different view of the same figure or object. To make sure this happens, the positions of the two shots should be at least 30 degrees apart from each other (along the 180 degree arc described above). See the image below from “BSL Sign for 30 Degree Rule”:

Here is a video on the 30 degree rule; you don’t have to watch the second half since it covers about how to film interviews—you just need to know about why filmmakers follow this rule and what happens when they do not. Plus, at one point, he says that breaking the 30 degree rule “creates a jump cut between scenes.” I believe he misspoke and meant to say “a jump cut between shots”:

At some point in the scene, perhaps multiple times, the editor will cut to a reestablishing shot. Reestablishing shots are shots that clarify the original space shown in the establishing shot. They do not have to be an exact copy of the establishing shot. For example, let’s say that your establishing shot is of busy office. It is mostly likely a full or long shot in order to show enough of the space to make it clear where the action is occurring (perhaps the master shot). You then begin to edit the scene, using shot/reverse shots, eyeline matches, etc. A character gets up and moves while talking. At this point, you may need a reestablishing shot so that the viewer is not confused as to where the characters are in relation to each other. The reestablishing shot may be a simple two or three-shot; it usually is a camera distance that reveals enough of the space to keep the viewer from being confused. Once again, it does not have to be an exact copy of the original establishing shot or the master shot. Please note: if you cut a new scene/new location, it is not a reestablishing shot but a new establishing shot for a new scene—this is a common mistake.

Continuity editing follows this basic pattern: establish/breakdown/reestablish. You first establish the space. You then “breakdown” the space or carve it up with edits. Characters will most likely move around as well, which will complicate the viewer’s sense of the space. In order for the viewer not to be confused and to maintain spatial continuity, you then reestablish the space with a reestablishing shot. You can then begin to breakdown the space again, following this pattern until the scene ends, and you begin with a new establishing shot.

As an exercise, take a look at his scene from Sullivan’s Travels, paying attention to how the scene follows continuity rules: setting up the space, breaking down the space, reestablishing the space (and repeating).

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/pfgonder/clips/continuity-editing-in-sullivans-travels/view.

In the first question of Exam 2, you will edit a scene following Hollywood invisible editing/continuity rules. Make sure you specify the establishing shot of the scene or any new scene. You should discuss the 180 degree rule and the axis of action. You should also include several reestablishing shots. Be sure not to confuse a reestablishing shot of the existing scene with an establishing shot starting a new scene.

Moving Outside the Master Shot in Continuity Editing

There are edits that take us into spaces outside of the master shot but do not violate continuity editing. The first of these is the cutaway. Like the insert, the cutaway is a vexed term, and you will find quite a bit of disagreement between sources about its meaning. For this class, we are going to define it as the follows: an edit to an object or person not in the master shot. In contrast, an insert cuts to something in the master shot (a body part, an object, etc.). A cutaway shows us something not in that space and perhaps not in the same time frame. For example, the cutaway may be psychological in nature; shot A is of a woman looking at a picture of someone while shot B is of both of them walking on a beach, in some other place, at some other time. Shot C returns us to the woman looking at the picture. Dissolves may be used here to signal that we are moving into a memory or fantasy and then back to reality. A cutaway may be simple as showing us something that is not in the exact master shot but is nearby. For example, the master shot may be of a young boy standing outside a school, waiting to be picked up by a parent. To emphasize that the parent is late, we could cutaway to a clock on the school’s tower (present in the same space but not shown in the master shot) and then back to the young boy. Notice that the cutaway edits back to some part of the master shot. Here is a good, succinct discussion of the difference between a cutaway and an insert:

Cutaways can also work as elliptical edits (for the sake of clarity, we are going to call this particular kind of edit an elliptical cutaway). An elliptical cutaway skips over time by cutting briefly to another scene or location and then back to the main action. For example, imagine your shot is of a writer working in front of a computer. To show the passage of time, you might cut to kids playing outside her apartment or cars going by his house. You then cut back to the writer, having just finished her work.

Please note that insert and cutaway are contested terms, and you may find other definitions in other sources.

A more complex editing technique (and one of the oldest) is crosscutting, which is sometimes called parallel editing. Crosscutting occurs when the editing cuts from one geographical space to an entirely different space and does rhythmically, back and forth. You often see crosscutting when filming phone conversations, but the technique is most often used to create suspense. D.W. Griffith did not invent crosscutting, but he was a master at its use (see the clip below).

Here are various examples of crosscutting:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/bnd/clips/crosscutting-in-d-w-griffiths-the-lonedale

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/bnd/clips/crosscutting-in-radio-days-1987

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/pcote/clips/sweeney-todd-crosscutting.mov

Some sources will draw a distinction between crosscutting and montage (see the definition below) by defining crosscutting as only involving two locations; more than two locations and it becomes a montage. For some scholars and filmmakers, the last example above (from The Godfather) is a montage, rather than crosscutting, since it involves several different locations and points of action.

It is possible to have a montage in a scene without violating continuity rules, but it is better if we discuss montages after we cover the Russian Montage Movement.

The Russian Montage Movement/Alternatives to Continuity Editing

We have been mentioning the Russian Montage Movement off and on through this section on editing, and they were certainly influential in the development of film editing, with the movement lasting from the 1920s into the 1950s. We will discuss these filmmakers in more detail in class, but what is important at this point is the way in which they admired, copied, and then broke into wonderful pieces the Hollywood continuity system. Soviet Montage created an editing system that could create continuity when necessary but was not limited by the need to maintain it.

For the Russian Montage Movement, “suture” was not always necessary or even preferable. Suture refers to how continuity editing “stitches” the viewer into the scene, giving them a clear position as a spectator. This position is meant to feel natural, with the editing working in a seamless way that does not disrupt or foreground the viewer’s experience. Suture means that we do not notice the edits; they are invisible. The Soviets felt that, at times, being “sutured” meant being hypnotized by the film; it meant you were watching but not thinking. Instead, they experimented in what some critics call alienation effects that create distanciation. Distanciation occurs when the edits become noticeable and are prompted to reflect and think about what we are watching. Alienation effects are cinematic techniques (in this case editing) that force a viewer out of a passive position as spectator and makes them consider what they are seeing on the screen. Continuity editing makes the edits invisible so that the viewer is sutured into the experience of watching the film; alienation effects break continuity rules and fracture spatial and temporal continuity in order to make the edits visible and to create an intellectual reaction.

It is important to note that the Soviets were not the only filmmakers or film cultures that developed different models of editing and that they did so for all different kinds of reason. Some of the examples below come from the great Japanese director Ozu, who was willing to break the 180 degree rule when the needs of a scene demanded it, and John Ford—the most American of American directors of his age—would do so as well.

Some sources refer to practices that diverge from continuity rules as discontinuity editing. I do not like this term since it implies that continuity editing is correct or the normal way to edit, and these practices should be defined in relation to their deviation from that norm. I would maintain that this is true in some cases, but in others, the edits described below represent an entirely different way to edit, rather than a reaction to Hollywood classical editing.

It is also important to note that some of the edits described below may not seem as discontinuous as they did in the past. Since the 1950s (and before then, in isolated but interesting cases), Russian style editing has merged with Classical Hollywood editing, with editors increasingly mixing the two.

One common practice in the work of these filmmakers and film movements is a willingness to break the 180 degree rule (“jumping the line”). In this clip from Tokyo Story, Ozu breaks the 180 degree rule; notice how screen direction changes.

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/tokyostoryexample.mp4/view

jump cut

A jump cut occurs when two different shots of (roughly) the same object or actor are too similar (see the 30 degree rule above). This creates a “jump” or break in the film, as if frames are missing. The action appears fragmented and broken. A perfect example of jump cuts from Godard’s Breathless: http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/breathless-jump-cuts.mp4

In this clip from the great television series Homicide, the director uses jump cuts near the end to signify the heightened emotions of the scene:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/jbutler/clips/Homicide193330131qq00_43_31qq.mpg

Be careful: a jump cut is not when a shot jumps to a new location. This is a common mistake. In fact, a jump cut is just the opposite; it is two shots of roughly the same action or object, editing together to create a jarring effect.

nondiegetic insert

A nondiegetic insert occurs when a filmmaker includes a nondiegetic shot, meaning a shot that is not part of the film’s narrative world. Nondiegetic inserts usually operate to make a metaphorical point. For example, in his film October, Eisenstein cuts from workers fleeing for their lives from government forces to bulls being slaughtered, and then back to the workers. The cattle are not part of the world of the film; they never appear in the movie, except for this one sequence. Another example: let’s say that you are very bored during my class, and I am rambling on. Imagine cutting to my face, then to a tiny, barking dog, and then back to my face. Nondiegetic inserts are often examples of what Eistenstein called “intellectual montage” (here we are using “montage” as meaning editing) in that they create ideas through the (visible, non-seamless) collision of the nondiegetic aspect with the other diegetic shots.

overlapping editing

Overlapping editing refers to when editing prolongs, extends, or repeats a certain action or moment to the point that it becomes clearly noticeable to the viewer. In Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing, after a character has been killed by the police, another character throws a garbage can and shatters a window; it is the climatic moment of the movie when pent-up anger finds release. Lee shows the can hitting the window and then repeats that same cut again. The overlapping editing at this point repeats the action:

Earlier in the same film, Lee uses overlapping editing to show a kiss:

Overlapping editing can do so by repeating the exact same cut or by showing the same action from another angle, perhaps multiple times.

An example of overlapping editing from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/potemkinoverlap.mp4

Another example from Soderbergh’s The Limey:

http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/ogaycken/clips/limeyoverlap.mp4

If you are interested in the films of Jackie Chan, check out this interesting video in which Chan talks about how he uses overlapping editing when creating his fight scenes, but he does so in a way that does not violate continuity editing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1PCtIaM_GQ

smash cut

A smash cut is when two shots are brought together for their contrast to each other in order to create a jarring effect. Most often, smash cuts act as (abrupt) transitions between scenes. You can think of a smash cut as the opposite of a graphic match; instead of cutting on powerful similarities, you are cutting on powerful differences. These differences may be color, camera distance, etc., but the transition between the two shots needs to be noticeable and jolting. Some filmmakers create a smash cut by cutting in the middle of dialogue or by cutting from loud noise to silence. Some will “smash to black,” meaning they will cut abruptly to a black screen.

Smash cuts may be used for comic effect. A common smash cut is ending a scene with a character loudly protesting that they will not do something and then cutting to the character doing the very thing they were vowing not to (sometimes called a Gilligan cut). Please note that we could take the prior example and make it a graphic match instead of a smash cut; we could cut to a close up of someone saying they will not go to the beach and then cut to the same close up of the character now at the beach. What would make this a smash cut is if the difference between the two shots are sufficient to create a jolt. For example, we could cut to the same close up, but cut off the character in mid-sentence, and we could make shot A darkly lit and shot B very bright.

Here is a very short but effective example of a smash cut: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=27jtM_jqnSA

I would warn you that many (even most) of the examples I found online where inaccurately labeled as smash cuts when they were examples of other types of edits.

flash cutting

Flash cutting means to join very short segments of film so that the combined footage “flashes” before the viewer’s eyes. The editing may be so quick that the viewer can barely make it out. In most cases, flash cutting disrupts continuity rules of editing, although it does not have to; continuity editing can handle fast cuts, as long as they are done carefully within the system (see any well edited action scene). In the case of flash cutting, the cuts are done to disrupt the viewer or to create a chaotic effect. Edgar Wright is the master of the flash cut for comic effect. Check out these examples from Sean of the Dead: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4YY6mymW4oA

If you are interested in the works of Edgar Wright, here is a great video essay on how he uses editing and sound to create comedy:

We will see some fantastic examples of flash cutting when we watch “The Odessa Steps” sequence from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin.

flash forward

See definition above. Flash forwards tend to disrupt temporal continuity while flashbacks do not. The difference here may have to do with memory. We are accustomed to “flashing back” to past events in our daily lives; we do so constantly as we remember the past (both recent and distant). We do not see the future—unless you are a mystical seer of some sort—and cutting to the future and then back to the present usually disrupts the viewer’s sense of linear time.

intellectual montage

Eisenstein used the term intellectual montage to refer to editing that exists to create an idea, to stimulate thought (for example, the example for nondiegetic insert, concerning the slaughter of the bulls as a metaphor for the slaughter of the soldiers). This term uses “montage” as meaning “editing.”

The Russian Montage Movement also used tonal montage, images that are edited together to create an emotional effect. Here is an example from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin; the shots of the fog/mist are meant to invoke sadness at the death of one of the sailors: http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/m_friers/clips/battleship-potemkin-tonal-montage/view

As an exercise (just as you did above with Sullivan’s Travels), take a look at the opening of Soderbergh’s The Limey in terms of how it breaks continuity rules, especially after the opening credits end.

Montage as a Sequence of Shots

Now that we have explored both Hollywood continuity editing and alternatives to this system, it will be easier to understand the idea of “montage.” To begin, it is important to note three different meanings of the word “montage.”

- In French, montage means editing itself.

- In terms of film history, Montage (with a capital “M”) refers to a specific movement: the Russian Montage Movement.

- In the language of American film production, montage refers to a sequence of shots.

This section focuses on definition #3: the montage sequence. The montage sequence refers to a series of shots that are clearly separate from what precedes and follows it. This sequence of shots often begins with a musical cue (a piece of music that signals a narrative change) and may be set to music. Some film theorists will differentiate between American and Russian style montage sequences. Here is the easiest way to remember the differences:

American style montages are always elliptical in nature; they push the narrative forward and condense time. For example, take a look at the montage that begins Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz. The film begins with a shot of the protagonists walking toward the camera; note how the music signals the start of the montage, which condenses the characters meteoric rise in the police department:

There is a particular type of American montage called a “training montage,” which you probably have seen many times. Here is a great parody of training montages from South Park:

http://www.comedycentral.co.uk/south-park/videos/sports-training-montage

Russian style montages differ from American style montages in that Russian style montages do not condense time. Instead, they drag out time or hold the narrative still. The purpose of a Russian montage is not to push the narrative forward but to create an intellectual or emotional effect (see intellectual montage and tonal montage above). For an example, check out this montage from Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. In this clip, Nichols crosscuts from Ben floating in the pool to him meeting his lover (Mrs. Robinson, his parent’s friend) in various hotel rooms. The purpose of the montage is not to advance the plot but to communicate the idea that Ben is lost, floating, aimlessly. Notice as well how Nichols cleverly plays with the Kuleshov effect and matches on action (which end up not to be matches on action) to confuse the viewer as to where Ben actually is.

https://criticalcommons.org/view?m=TqWeWzWE2

Works Cited

“Insert.” Wikipedia. 17 Feb. 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Insert_(filmmaking)

“Master Shot.” Wikipedia. 17 Feb. 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Master_shot