The following is a supplement to Sharman’s chapters on mise-en-scène and acting. Mise-en-scène and cinematography blur together somewhat, so you will have to skip between these two chapters in Sharman’s book. Sharman mentions lighting in his chapter on mise-en-scène, but we will regulate lighting to the next set of readings on cinematography (most scholars put it under that heading). Sharman discusses camera distance and frame composition in his chapter on cinematography, but we will discuss them under the umbrella of mise-en-scène. I am making these distinctions partially to make the two lists balanced in terms of the numbers of terms and the level of difficulty.

At times, in defining a term, I may speculate on the effect of that technique on the audience, especially when I discuss specific examples. I am not trying to be reductive—something we should avoid, always—and asserting that everyone will see this example in this way or that this technique always creates said effect. We must always remember that any given technique must be analyzed in relation to other formal elements, including the plot of the movie. For example, low angle shots can make a character appear large and imposing, powerful. Yet, in a famous scene in Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane (1941), the character of Kane has smashed into the upper limits of his political power; he has been defeated in a crucial election due in large part to his own hubris. Welles shoots Kane (played by himself) from a low angle, which does not make him look powerful—we see the heavy, somewhat ornate ceiling above him, symbolizing that this is as far as he will rise (see the picture below and the link to a clip):

Before we grapple with the terminology, let’s discuss some conceptual matters, specifically the difference between what scholars call naturalism and expressionism.

In class, we will discuss the problem with the term “realism” and why it should be avoided as a strict criterion for judging a film. We will also discuss how to view film as a system of interconnected formal elements, these elements being represented by the entirety of the terms and concepts we will study this semester. In order to understand how film works and what it creates, we have to be able to know and name these elements.

Sharman will discuss the difference between “naturalism” and “expressionism”/ the “theatrical” traditions. Since these are key concepts for Exam 1, we will spend a little more time on these concepts here.

Instead of “realism” or “realistic,” we will be using the term “naturalism” or “naturalistic.” The naturalistic aesthetic (by “aesthetic,” I mean an artistic vision or plan) attempts to capture lived reality in a way that seems true or authentic, without exaggeration. On Exam 1, you will write your first answer following a naturalistic aesthetic.

The expressionistic/theatrical tradition tries to capture not the reality of lived experience but its emotional truth. A film that uses this aesthetic is much less concerned with accuracy and more with conveying what the experience means or the feeling generated. It does not break from reality as much as bend, exaggerate, or distort reality in order to more accurately convey it. On Exam 1, you will rewrite your first answer (in which you follow a naturalistic aesthetic) as if you are member of the German Expressionism movement. German Expressionism is a film movement (see the definition below) that began around 1919 and ended somewhere in the late 1920s or early 1930s. The major directors working in his movement include Robert Weine (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari), Fritz Lang (Metropolis), and F.W. Murnau (Nosferatu). The related movement French Impressionism had its heyday throughout the 1920s with Abel Gance (Napoleon) being the preeminent director. While there is some debate as to whether either of these are true film movements, their influence is undeniable (just take a look at any Tim Burton film for proof of that). In class, we will expand on Sharman’s discussion of this movement. Here’s a link to a short video explaining the history and nature of German Expressionism:

Throughout the semester, we will discuss different “film movements.” A film movement (not to be confused with “camera movement,” which we will discuss under cinematography) is a term that film historians use to describe what happens when filmmakers in roughly the same geographic area, working under roughly the same cultural/historical factors, make films that clearly can be grouped together. These films share some kind of common aesthetic strategy in regard to how they “look” and may also share thematic or narrative similarities

locations and location scouts

Film productions may choose to film on location (rather than on a soundstage). Location scouts are those individuals who are involved, primarily, in the preproduction of a film. They find locations that might work for various scenes in the film, usually presenting the director many options from which to choose. They also negotiate with local governments, unions, and private homeowners. During production, they are trouble-shooters, who have to deal with the eventual problems that arise with the location. It is a difficult and fascinating job.

Even if a film shoots on location, mise-en-scène still comes into play since this location was chosen for specific reasons, and the production designer and the art department will “dress” the location (make changes both minor and major). People tell horror stories about allowing their homes to be used for film shoots only to find that the filmmakers want to repaint rooms or even tear down walls!

A great way to get started writing Exam 1 is to consider your set or setting. Are you choosing to film on location or on a soundstage and why? What tone or mood is your production designer and set decorator trying to create? Do you need to use a green screen to create an artificial environment/setting?

prop as motif, metaphorical props

As Sharman states, “Every object placed just so on a set adds to the mise-en-scène and helps tell the story.” For the sake of this class, please remember that not every object should be considered a prop—only those that are of some kind of importance or play some kind of role (even if that role is subtle and not noticed by the viewer).

Props become a motif when they take on additional meaning with repeated appearances over the course of the narrative. Imagine a movie in which roses appear at multiple times during the course of the film; each time the roses appear in the shot, the characters experience some form of emotional turmoil. The roses become a motif, linked to a certain idea or emotion. A metaphorical prop does not have to be a motif in that it may appear only once in the film. Consider a scene in which the main character tries to grapple with the upcoming death of a loved one. In the foreground, a large, ornate clock sits, its face turned toward the audience. You could make the argument the clock is a metaphorical prop, representing the unstoppable movement of time.

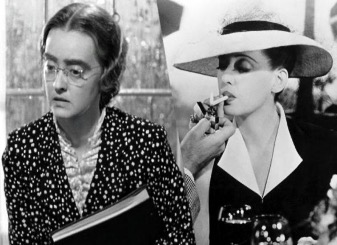

Edith Head (see image below) fought for years to have costume design included at the Academy Awards and then won the first eight Oscars given in this category (plus, she is clearly the inspiration for Edna Mode in The Incredibles).

costume and costume designer

Costume refers to intentional choices that a filmmaker uses when choosing what a character wears, and these choices are often made by a costume designer. As in props, not everything a character wears may be important—sometimes, pants are just pants—but costuming (and the choices that a costume designer makes) can have a powerful and immediate influence over how the viewer sees the character. In a documentary, the filmmakers cannot choose what the people in the scene wear—most often, they are capturing something as it happens—but what these people wear still has an effect on the viewer.

make up artists

Make-up may not be as noticeable as costuming but is just as powerful. It may not be noticeable since make up artists often labor to make their work invisible. If a character looks like they are not wearing make-up, there is a decent chance that they are wearing make-up designed to create a “no-make-up” or natural look. Make-up can also merge with special/practical effects; make-up artists have been asked to make actors look much older or transform them in monsters.

Dick Smith was the master of aging effects, and he also created the horrific make-up for The Exorcist. Tom Savini specialized in creating wounds while Rick Baker has won seven Academy Awards for his work in make-up and other special effects

Take a look at the following image—a still of the four main characters from Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden (2016)—what do you know about them only from their style of dress and make-up. What do assume about their personalities or their relative positions of power?

Take a look at these two stills below from Now, Voyager (1942). In the left, we see Charlotte at the start of the film; at this point, she is dominated by her overbearing mother. On the right, we see the same character after she has asserted her individuality and found her own identity. Note the extreme difference in makeup and costume that signals this radical change. Plus, Bette Davis—the legendary actress who plays Charlotte—communicates the shift in character through facial expression and body language. Notice how props such as the book she clutches to her chest vs. the wine glasses in front of her communicate a new-found freedom.

We can think of these details as character highlights, which is any aspect of mise-en-scène that reveals something about a character’s personality or nature. Mise-en-scène can also act as a narrative marker. Narrative markers work to show the passage of time. The change in costume and make up below signal a movement forward in time as well as a change in character.

Another easy way to get started on Exam 1 is to think about the costume and make up design of your main character or characters. Focus on elements that matter, that communicate something about the character or their situation. Think also about the color design of the scene and its effect on the tone of the film.

color, and color design

A key factor in set and costume design is color. Take another look at the frame from The Handmaiden above. From color alone, what assumptions can you make about these characters and their relationship to each other. Notice how the only vivid green of the woman’s dress to the right makes her stand out as different from the others.

Limited palette refers to when a filmmaker uses only a few key colors within a given scene. Monochromatic color design is when a filmmaker only uses one or two colors (and it is not a black and white film). Here is an example from Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) in which director Guillermo Del Toro uses only shades of orange and red.

Limited palette and monochromatic color design should be somewhat severe and striking (as in the image above from Guillermo del Toro’s masterful Pan’s Labyrinth). When writing Exam 1, save these terms for the second answer in which you are employing expressionism. In your first answer, you should use color in a more naturalistic way; you will still have an overall color design, and you may limit your use of color for an expressed purpose. However, in your first answer, this color design will be more subtle; in the second answer, you can then exaggerate these same choices.

Camera Distance, Angle, Height, Level, and Position

Sharman discusses camera distance, but it may be helpful to go through it again, with more examples.

The distance between the camera and the object of focus plays a crucial role in shaping how the viewer may react to what they see on screen. It is important to think about the effect of moving or editing from a close up to a long shot (or vice versa). What is revealed that was previously unseen as more of the surroundings come into view? What details are emphasized when the camera moves in close? Quick note: these terms usually applied to the human figure, but we could also use them to describe the camera’s relationship to an object as well (if that object is the focus of the shot). Here is a helpful diagram made by Flávio Pádua.

For sake of simplicity, I will use a human figure for the examples below. Remember that any given shot may fall somewhere in the range between these terms, and you can combine the terms to be more accurate. Plus, camera distance is just that—a matter of distance, not visibility. In the frame below, we only see the woman’s eyes, but we would call this a close- rather than an extreme close-up since we are at that specific distance; if it was not for the window and lighting, we would see her entire face.

extreme close-up

The camera is positioned extremely close to the object or person. Example: a shot of a doorknob that fills the screen. You often see extreme close-ups of just one eye or both:

Tarantino loves extreme close-ups of objects and faces; here is a super-cut of examples from his films:

choker

A shot that captures the face from about the eyebrows to the mouth; it is somewhere between an extreme close-up and a close-up (see below):

close-up

The entirety of the human face fills the screen. Here is a shot that is somewhere between a choker and a close-up from Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color (2013):

medium close-up

A shot that is about a 1/3 of the human body (for example from the chest to the face or feet to mid-thigh). The shots from Pan’s Labyrinth or Now, Voyager above are medium close-ups.

medium shot

From the waist up (or down).

medium long shot

From the knees up or about ¾ of the human body. An American shot is a three-quarter shot of a person, from the knees up. This shot was named by filmmakers outside the United States who noticed that, in the early days of cinema, American directors and cinematographers tended to use this camera distance when filming people.

full shot or long shot

A long or full shot is the entire human figure captured

wide shot

At times people will use long shot, full shot, and wide shot interchangeably, but some experts use wide shot to refer to something more specific: a long shot of a person or object paired with a wide aspect ratio and/or a wide angle lens (which increases the sense of depth within the shot) so that the relation between the figure/object and the surroundings are emphasized. We will talk more about aspect ratios and lens in the next set of terms. Here is an example of a wide shot from Truffaut’s 400 Blows:

Here is another from Ciro Guerra’s The Wind Journeys:

extreme long shot

The camera is far back enough so that the surroundings dwarf the human figure. Here is an example from Iñárritu’s The Revenant:

angle, height, and level

Angle and height matter as well as distance. First, consider the height of the camera. Is it eye-level (which is common) or is it at a higher or lower position (once again, the human body is usually the frame of reference)? Next, what is the angle? Most of the time, the angle will be “normal,” which is to say, no angle at all. A high-angle shot means that the camera points downward; a low-angle shot is looking upward. A bird’s-eye view is an extreme high-angle shot so that the viewer is looking directly down at the object of focus, from above the object. Notice that you could have a low-angle shot paired with a high height or a high-angle shot paired with a low height (for example, a close up of a pair of shoes, filmed from a low height but looking down on the shoes from a high angle).

In addition, consider level. The vast majority of the time, the level of the camera is true to horizon. A canted angle (sometimes called a Dutch tilt) means that the camera has been tilted to one side of the other. Here is a Dutch tilt from DePalma’s Mission Impossible. Note how the character’s face is not level with the frame:

two-shot, three-shot

Simply put, a two-shot is a shot of two people; a three-shot is of three people.

over the shoulder shot

When the camera is positioned as if it is behind someone, with their shoulder (or more of the body) entering the frame as we look at something or someone in front/past them.

When writing Exam 1, you will want to specify the position of the camera in relation to the action. It is here when you can use the terms relating to camera distance and position. It is important to keep in mind where the camera is located and what is being shown at any given time.

The Composition of the Shot

Sharman discusses the composition of the shot, the placement of key figures/elements in relation to each other and to the environment of the shot. This aspect of mise-en-scène points to the (often underestimated) influence of painting on film art. The frame of the screen can be imagined like the frame of a painting and is just as carefully composed. The frame can also be imagined more like the frame of a photograph (as if the frame were a window). The first concept (the painting) tends to create a closed frame, with elements contained within the limits of the frame; the second concept (the photo) tends to create an open frame with elements extending offscreen.

The open frame brings out the excitement and chaos of this particular moment in the film. Now, contrast this shot with one below from David Cronenberg’s A History of Violence (2005):

While elements extend off frame (the bodies of the couple closest to the camera, for example), notice how the walls and doors emphasize the limits of the frame. The family shown here seems connected, but the space also has a claustrophobic feel.

compositional balance and imbalance

Are key figures placed in symmetrical, even mirrored positions, creating a sense of balance? Is one side of the frame “heavier” than the other? We usually use compositional balance to refer to lateral positions within the frame, rather than depth, although depth could have an effect (see the shot above from A History of Violence). Note the difference in the two images taken below (both from Wong Kar Wai’s Chungking Express). The first frame has compositional balance while the below is more imbalanced (and is another example of a canted angle/Dutch tilt).

Sharman discusses negative space, but it may be helpful to have an example. Negative space refers to the use of empty space within the framing of a shot, often (but not always) used to create a compositional imbalance. Check out this frame from the BBC series Luther:

Below is an example of negative space used to create a balanced composition. Note as well that balance does not necessarily have a positive connotation. In this frame from John Ford’s The Searchers, the character appears isolated and alone, trapped despite the open space behind him:

So far, we have focused more on the lateral aspects of the frame; let’s talk about depth.

planes

When discussing depth, we will refer to the different planes in a shot. Each plane is a layer of depth within a given shot. If you have a frame of a woman standing in front of a line of trees, with buildings in the distance, you would most likely have three planes (the woman, the trees, the buildings). The image from The Searchers has three to four (the wall/door, Ethan, the ridge behind him, and the mountains in the distance.

depth cues (overlap, aerial perspective, size diminution)

Depth cues are the means by which a flat 2-dimensional image appears to have three dimensions. Overlap is simply the way in which we see something as closer if it is in front of something else. Aerial perspective is a matter of focus; things that are farther away tend to be out of focus and blurry, as if you are looking into the horizon. Finally, size diminution refers to how things that are farther away appear smaller.

In the frame above, the mountains in the background are slightly out of focus (aerial perspective); Ethan (John Wayne) overlaps the rocks behind him (overlap); and finally, he is smaller than the frame of the door (size diminution)

I often say that the film gods are cruel in that some of the terms have potentially confusing names. A common mistake is to confuse “aerial perspective” (the depth cue) with “bird’s eye view” (when the camera is positioned above the subject) or to mix up “deep space” and “deep focus.” Be careful not to do so.

shallow space vs. deep space composition

Shallow vs. deep space composition is not a matter of focus but more so the sense of depth in a shot, or the lack thereof. In shallow space composition, the planes appear to be stacked on top of each other, like a painting. In deep space composition, many times through the use of depth cues, there is a sense of depth to the shot. Do not confuse deep focus with deep space composition. Deep focus is when every plane is in focus; you can have deep space composition without deep focus.

Check out this clip from All the President’s Men for the difference between shallow and deep space composition; the clip begins in shallow space and moves to deep space as the reporter gets “deeper” into his research:

rule of thirds

Rule of thirds can be a tricky concept. Here is an additional definition: “The rule of thirds is a “rule of thumb” or guideline which applies to the process of composing visual images such as designs, films, paintings, and photographs. The guideline proposes that an image should be imagined as divided into nine equal parts by two equally spaced horizontal lines and two equally spaced vertical lines, and that important compositional elements should be placed along these lines or their intersections. Proponents of the technique claim that aligning a subject with these points creates more tension, energy and interest in the composition than simply centering the subject” (“Rules”). Here is a nice video explaining the concept as well:

When writing Exam 1, it is a good strategy to pick a few key moments and consider intently the composition of that image, thinking more like a painter than a filmmaker. Consider the blocking of the key elements within the frame (human or otherwise), their relationship to each other, to the frame itself (is it an open or closed frame?) and finally the sense of depth within the shot (or lack thereof). Whenever you can, describe why you are making these choices and the effect they may have on the meaning of the image.

In terms of depth, always consider what planes are in the shot. Doing so will help immensely as you include the cinematography terms.

Sharman discusses blocking, how figures are placed “on stage,” where characters stand or move in that space and their relationship to each other. It will be helpful to consider two more specific kinds of blocking in film: graphic blocking and social blocking.

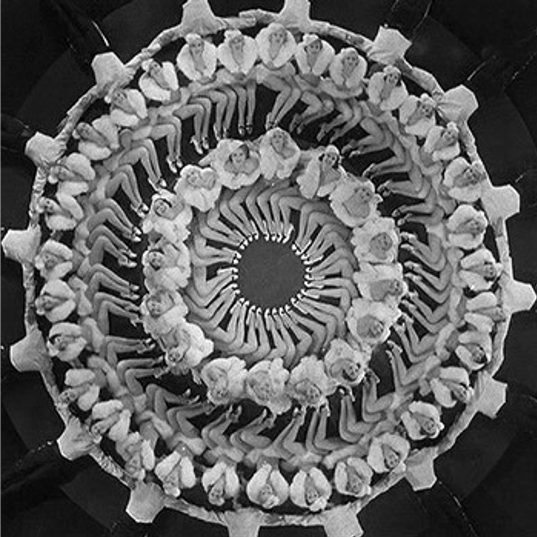

Graphic blocking occurs when characters are arranged in geometric shapes or patterns. Here are two stills that illustrate graphic blocking; the first is from a Busby Berkeley musical (a director famous for using wild examples of graphic blocking) and the second is from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (see also the still in Sharman’s chapter) in which Lang combines graphic and social blocking to show the depressed state of the workers in this futuristic city.

Social blocking is when this placement carries a meaning in terms of social or personal relationships (for example, a character in power being placed in a higher physical position; individuals who are opposed to each other being placed on opposite sides of the frame). The still frame from Metropolis is an instance of both graphic and social blocking.

frontality

Frontality refers to the propensity of the viewer to notice objects or actors that are facing the viewer. It does not refer to being in the “front” of the shot. For example, imagine a shot of people passing laterally in front of the camera, with their faces turned to either side of the frame. Behind this crowd is a woman more or less facing the camera. Even though the viewer only sees her intermittently, in the gaps of the crowd, the viewer’s eye may be drawn to her since she faces the camera.

accents

Accents are points of movement within a shot. Generally, more accents/movement in the shot accelerates the viewer’s sense of time passing while fewer accents slow down the perception of time.

Acting and Performance

Sharman’s chapter on acting is excellent, in my opinion. Acting remains one of the hardest aspects of film art to discuss since it is one of the most ephemeral and fluid. Unlike color or composition, it is hard to quantify. Plus, as Sharman points out, what defines “good acting” has changed radically over time. An individual film may demand a certain kind or style of acting that would fail in another movie. In this way, acting teaches us something key—any given film technique has to be understood in relation to the movie as an entire working system. What works in a non-genre drama from 2018 is not the same as what works in a silent Western from the 1920s.

Remember as well that it is difficult to analyze acting without including elements such as mise-en-scène, editing, sound, and cinematography since they will all influence how the audience perceives a given performance by an actor. An actor never performs in a vacuum; even if we only hear their voice, the blank screen will change the impact of what the actor says on the audience. We will discuss this idea in much more detail when we cover editing.

In any case, we will add a few terms will help us get a handle on this complex subject.

body, face, and voice

Many acting teachers will tell their students that they have three main tools in their kit: body, face, and voice. To understand an actor’s performance, we have to examine what they do with their body, face, and voice. We should not use the actual lines of dialogue they speak (unless the line has been improvised, the dialogue is a product of the screenwriter and screenplay), only how they say the line. Check out this video of the great Cary Grant (perhaps my favorite actor) from Arsenic and Old Lace in terms of how he manipulates his body, face, and voice. In this clip, he discovers a dead body in his beloved aunt’s home: http://www.criticalcommons.org/Members/pfgonder/clips/acting-and-the-body-in-arsenic-and-old-lace/view

Contrast this performance from what you saw of him in the opening of North by Northwest. You could argue that his performance in North by Northwest is more naturalistic while he takes on a more theatrical/expressionistic approach in Arsenic and Old Lace.

star actors and persona

A star actor is one who has developed a certain set of characteristics that they bring to every role, that the public associates with them, what is referred to as a persona. Star actors tend to play similar characters from role to role, and they will bring their persona to each one. For example, Keanu Reeves has a certain persona that the public expects and which inflects each role he plays. Of course, a star actor may choose a role that violates that persona in order to shock the audience. Plus, it is important to note that a star’s persona can change over time (think about how Clint Eastwood’s star persona has shifted over his decades long career).

This may be putting it too simply, but to remember the difference between these types of actors, think of it like this:

An actor from the “Classical School” plays the role. When I watch Denzel Washington play a part, he does not vanish into the role. Washington plays radically different roles, but the pleasure we get from his performance is watching him play that part, almost like a musician playing an instrument.

A method actor becomes/vanishes into the role. When someone like Meryl Streep takes on a role, she disappears; you forget that you are watching Streep and only focus on the character. Method actors tend to take on radically different roles, vanishing into each.

A star actor is the role; the role already fits or works with the characteristics or qualities known by the public. Tom Hanks has a star persona—the public links him to ideas of moral decency and a certain kind of modern masculinity (among other things). This is not the same thing as being type-casted; Hanks may play different roles (ship captain, hitman for the mob, etc.), but he brings these qualities to each part.

Works Cited

Pádua, Flávio. “Basic Types of Field sizes for Newscast Participants.” ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Basic-types-of-field-sizes-for-newscast-participants_fig3_318686299. Accessed 18 May 2020.

“Rule of Thirds.” Wikipedia. 17 May 18 2015. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rule_of_thirds.